The Ground Day Breaks

A solo exhibition by Muhannad Shono

curated by Nat Muller

ATHR Gallery (Riyadh)

Architecture fixes narratives, forcing belief, ritual, and story into rigid, immutable form. This permanence renders the form impossible to negotiate with. When the earth is compressed into certainty and function, meaning hardens into dogma. A structure that demands stability cannot be reinterpreted. Only when that structure breaks, when the stubborn earth collapses into rubble, does imagination unfurl. Rubble is architecture becoming human: fallible, open, unfinished. When architectural volume sheds its function, it yields to pure possibility.

Desert sand actively resists this rigidity. It cannot anchor itself in durable concrete; it repudiates the monolith, the icon, the monument designed to enforce a singular, lasting narrative. Architecture as fixed text fragments here, its authority challenged by the refusal of its own grain.

This carbon-fired desert sand, once compressed into industrial molds, served foundries until it was dismissed as spent and useless for construction. Shono retrieves this rejected earth and executes the ultimate counter-ritual: the mold is shattered. The mono-form breaks apart, and the material, released from purpose, surges into a state of restless potential.

A single imposed narrative fragments into a field of infinite readings. Grains scatter, cluster, and shift, refusing final geometry or singular meaning. Crucially, the breaking of the block creates interstitial space: a dynamic, fertile void between the particles where new meaning resides. In this condition, rubble is not ruin but a new form of authorship: the earth writes again through dispersion, impact, and the sheer movement of matter.

Material research becomes an urgent act of world-unmaking and world-making. What once held a fixed story is now an unfolding text shaped by erosion, line, and entropy. Every attempt to fix, confine, or finalize is destined to surrender to this truth: the ground does not hold; the ground breaks, and with it the imagination once sealed inside the block.

A Promise of Breaking

The print series, A Promise of Breaking, captures the exact carbon transfer of the block's violent impact. These impact prints register the singular moment a fixed body fractures, releasing the story once sealed within it. The break is a point of departure, shattering the monolithic narrative into dispersal, movement, and raw possibility.

The monolith now fragments into an infinite landscape of reading, unfolding into an imprint and an open narrative space between the pieces. The resulting imprint is an architectural blueprint, a story of interstitial action, a landscape built of infinite grains of matter and meaning. The gap becomes a threshold, the mark an opening, the pigment pure potential. The earth itself, the block's original material, reasserts its agency in this moment of release.

A Promise of Breaking holds a haunting sensibility, lingering in the void where form unfixes and meaning slips, where the block's former solidity explodes into potential. Nothing is static: the material, even its shadow, is mobile, fluid, and transformative.

From the Land

The motif of Al-Khidr, the Verdant One, offers a vital path for contemplating renewal and the greening of what appears inert. This mythic presence, a figure known widely across global traditions, moves in the lineage of Osiris, Attis, and Enkidu, archetypes often understood through cycles of death and resurrection. Yet here, the figure, like nature, is neither dead nor reborn; the conditions for a formal return are not yet set. The earth, instead, becomes the latent figure itself, present and immortal, awaiting activation in From the Land.

Here, the form begins with a break. A block is fractured, its rigid authority undone. The grain of sand, released from the definition and architecture of the mono-narrative block, is buried in itself, laid to rest in its own potential. This returns the material to ground: burial mounds are layered and relayered, actively multiplying into an ambiguous terrain that sits between wasteland and agricultural landscape. The earth is tended, irrigated not with water but with a natural binder, an irregular rhythm of spraying that binds and releases at once.

When these layers harden, thin skins are delicately peeled from the surface. The land gives up brittle forms that have been grown, weathered, and lifted. They stand as if exhumed: forms birthed by burial.

This process turns the ground into author. Irrigation becomes rebinding; rebinding becomes harvest. The earth is harvested for shape, then exhumed as nature’s own crop, a harvest of form as bountiful as grains of sand, an infinite field of forms and readings. Each piece is a remnant of a landscape that relentlessly rewrites itself.

Alien yet grounded, these objects arrive with the authority of something returned. They feel excavated and sprouted simultaneously, suspended in the unresolved space between scar and healing, soil and sky, form and its undoing.

Folding Grounds

This shapeshifting and mutable characteristic comes to the fore in “Folding Grounds” where large strips of coagulated sand are suspended from the gallery’s ceiling or draped into form. This work flows upwards and engages the viewer’s eye vertically. It emphasises the structuring and structural properties of the material, which harks back to how sand is used for construction. But rather than rigid towering builds, here the pliability of the material is key. There is a softness to these formations akin to textiles. Whether shroud, garment, or carpet the sand in Folding Grounds intends to provide comfort and shelter and inspire aspiration rather than veneration.

Seedlings & Night Dew

In Seedlings, a carbon transfer on paper, the grain blooms feverishly, trying to outgrow the frame as it seeds into spore-like forms that recall sand’s role in cultivation. Its twin, Night Dew, a series of carbon-paper lightboxes worked in stipple from memory, renders the grain as ghostly trails, fragile, luminous traces suspended between encroaching darkness and tomorrow’s light, like dormant seeds waiting to germinate. Together they shift from determined energy to latent possibility, revealing how each grain, each dot, remains distinct up close, yet merges into new patterns when seen from afar.

The Ground Day Breaks

Throughout the exhibition reclaimed sand features as a granular agent of change. This is most palpable in the exhibition’s titular piece, The Ground Day Breaks, a large-scale site-specific installation consisting of approximately 2000 handcrafted sculptures arranged in a radial pattern. Few artists manage to marry monumentality with tenderness and poetic sophistication. This is exactly what Shono achieves in this intervention. Scale immerses rather than produces spectacle. Ruin voices possibility instead of only disaster. The viscera of this piece lay bare; however, they do not overwhelm but weirdly enthral. It is in this parched garden with its skeletal irrigation ducts exposed that all falls apart and comes together. Everything swirls around an empty centre, a void. But from this nothingness everything radiates outwards and, conversely, is sucked back inwards. This two-way vortex should be impossible, but it is not in Shono’s world. With an energy that is subtle as much as it is defiant The Ground Day Breaks offers a broken horizon, but a horizon, nonetheless. This work strongly resonates with how Brahim El Guabli typifies the desert as both necropolis and life source, as a site that is “terrifying and edifying; dangerous and peaceful.” Shono presents us with an exhibition that encompasses all these contradictions and how they are enveloped in a tiny grain of sand.

What Remains

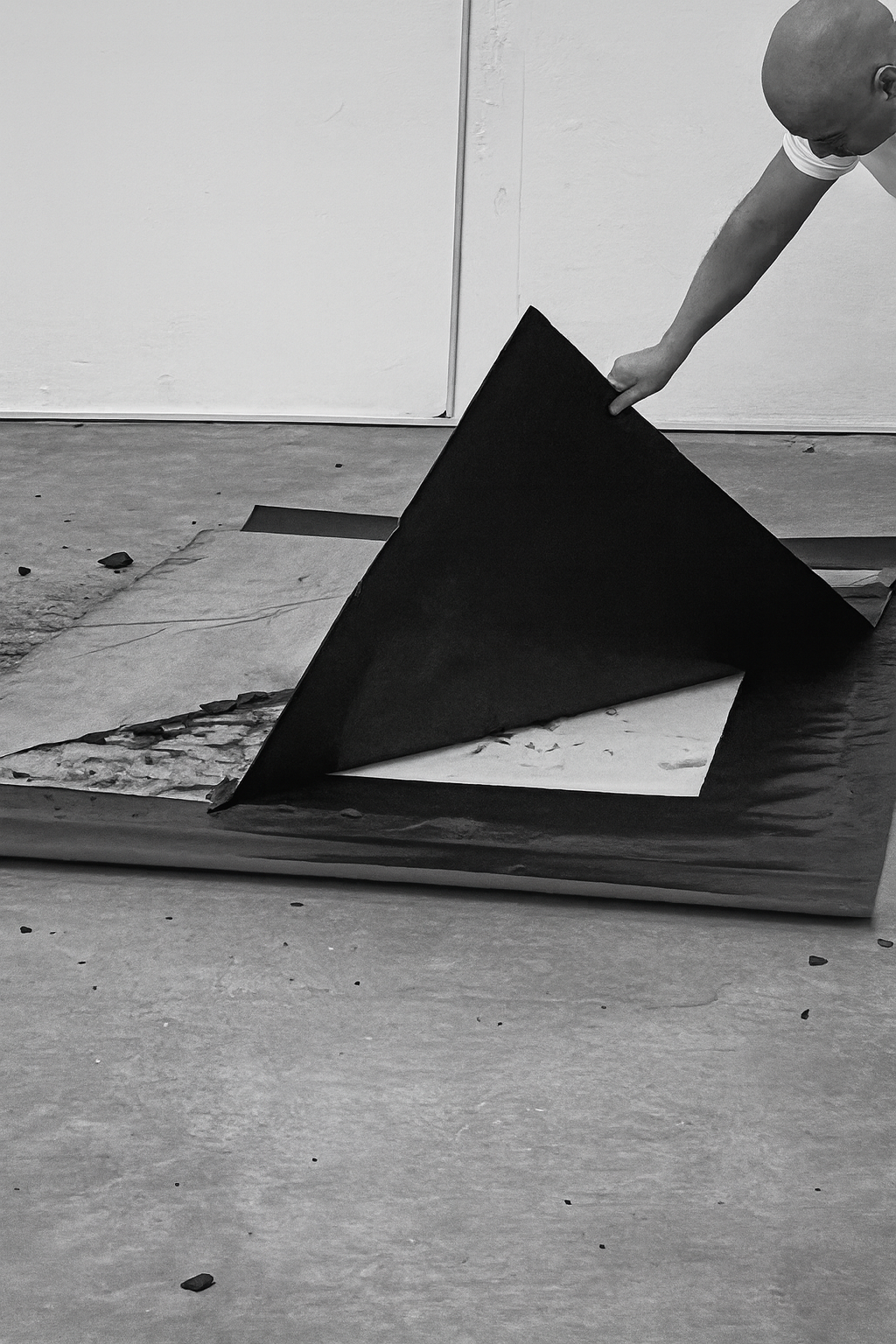

While renewal lies at the heart of this exhibition, in which a new day can break ground, it is not without violence and loss. This is, however, never absolute, and even through the rubble something generative can be found. If “From the Land” purports healing, then “What Remains” can be seen as the wound. Here we find the cut and the rupture: this is the moment everything changes. Blocks of sand have been broken on the floor or on the brown side of carbon paper, a colour reminiscent of desert sand, then the pieces are centred towards the greatest point of impact. This is material smashed to bits on a hard surface, but it also indicates how matter always retains a memory of its former whole self when broken. Here too it is unclear whether the grains want to dissolve further or come back into formation.

images courtesy from Artur Weber and Federico Acciardi and Sumayah Fallatah