The Silence Is Still Talking

A Solo Exhibition by Muhannad Shono

Curated by Rahul Gudipudi, at ATHR Gallery, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

We find ourselves today in a crisis of the word. The ‘word’ as we know it, has become restrictive, divisive, hardened, literal and unimaginative. To understand and respond to this crisis, Shono journeys us into a praxis of the word and a slowing down of the utterance of the word. His proposition is to reform each word object and study the oceans of nuance, laterality and metaphor that accompany these words.

He extends his practice of pigment on paper, grinds hardened charcoal words to dust and employs vibrations from inaudible spectrums of sound, to lend them back their voice. These specs of black pigment, are the nuance, context and depth of meaning that accompany each word as it reemerges. Black dust and flakes that bring matter and meaning together, and with each spec and the many probabilities of location and orientation of specs of pigment, they represent the infinite possibilities of meaning, like quantum states and also similar to accents in language that accompany alphabets and morph sounds and significance with their location. These possibilities embody the spirit of each word as opposed to the letters of the word, to be nurtured in their limitless arrangements of meaning. This use of vibrations to create the works, withdraw control and the notion of lone authorship away from the human hand. It celebrates the externality of the origin of the word, and propels us to consider the mind and the self as bodies that highlight, expose, interpret, transfer and preserve the spirit of the word.

The exhibition explores the infinite layers of meaning encoded in words and how they shape our experience of knowledge and understanding. Our relationship with the Earth being defined and formed with the words we choose to describe and traverse it. The process with which we arrive at the word, becomes the means through which we meditate on its use and exert ourselves towards constant cycles of reading and re-reading, learning and unlearning as practice. Shono’s artworks guide us to move away from literality and away from the adoration of textuality. The exhibition seeks to shift us from outcomes of misuse and misunderstanding towards the birth of a deeper understanding of the word, ourselves, others and the Earth.

The Hardened Word are hand-carved charcoal sculptures that are hardened and brittle words as we know and use them. They signal the literality of thought in words and the misuse of words and narrative to influence minds and bodies.

Of divisive and measured appropriation of texts and ideas, and the drying out of the moisture of nuance, laterality and metaphor that give life to thought and ideas in these words.

The word and language influence how we name and remember the world. They sculpt our imagination and the directions in which we labour to build it. Jean-Francois Lyotard speaks about the influence of language in enlightenment based production of modernity and how language influences the construction of our minds as well as physical and digital futures.

TO GRIND IS TO ERASE, TO ERASE IS TO CREATE

Charcoal forms like The Hardened Word are ground down to specs and dust. Into fundamental particles that embody the Matter of Meaning. The Matter of Meaning is the charcoal dust that acts like pigment throughout The Silence Is Still Talking exhibition, waiting to be revived and reanimated by the voice of vibrations and sound.

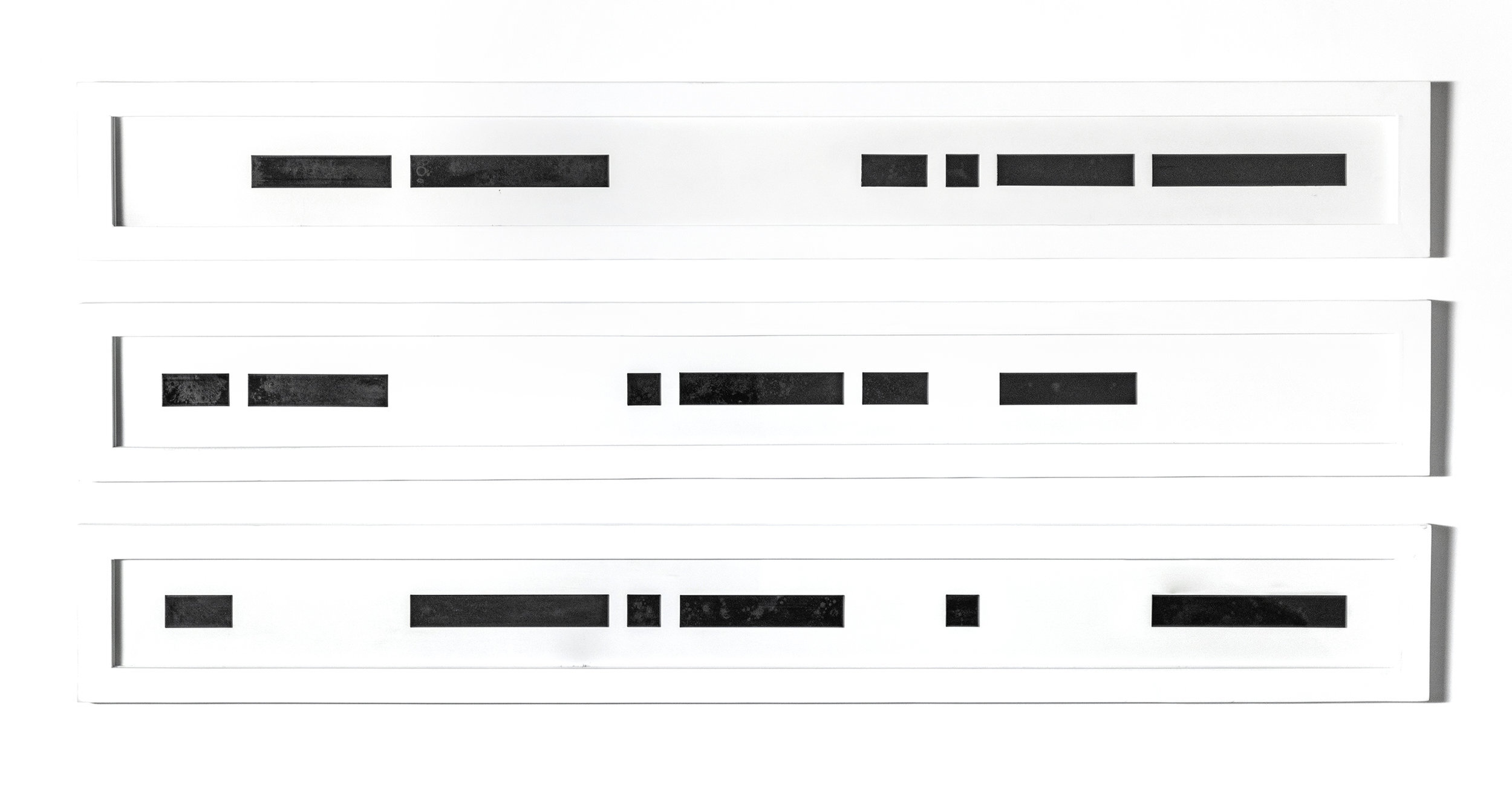

To Erase Is to Create, are 3 process works of abrasive tape and charcoal pigment. The act of grinding is not a violent act. It is an act of nurturance. A slow and repetitive or persistent action, as wind and water shape rock and land.

The Matter of Meaning

The Matter of Meaning, is a video installation, that gathers the pigment dust and specs that are the seeds and elements of meaning, waiting to be animated and brought back to life.

CHAPTER 1

THE BIRTH OF THE WORD

When we look back and study the footsteps of humankind, we notice an abrupt deviation in the development of our minds at the same time that we see the emergence of complex language systems. These systems that allow us to articulate infinite possibilities of thought through the finite means of utterance, vocabulary and grammar as noted by Wilhelm Von Humbolt, continue to astound us (and the best of linguists) even today. The human capacity to communicate intangible ideas through the creative use of language, association and the metaphorical possibilities of the word is a mystery yet to be understood. ‘The Word’ with such infinite creative potential, according to David Hume in the western world (and well documented unknown thinkers in the eastern world), is a mystery beyond our capacity for knowledge. The origin of the word is perhaps just as unknown or unknowable as the origin of the universe.

“At whose will does humanity utter speech?..

How can we with words, express that which expresses words?

How can we with our minds, think of that which moves thought?

How can we with our eyes, see that which illuminates sight?

How can we with our ears, hear that which enables hearing?

How can we with our speech, speak of that which allows speech?

How can an ant on a blade of grass, see the meadow?”

- Unknown, Kena Upanishad

The names of all things, a live-installation with charcoal dust and sound on paper, ignites our journey into the word with pigment and frequencies as source. The vibrations of pigment mark the paper and create a shifting source of infinite possibilities of meaning. All other works follow and are derived from this recurring process of pigment and vibrations.

CHAPTER TWO

THE WORD SPOKEN-UNSPOKEN, PERFORMED

Herman Parzinger’s book Die Kinder des Prometheus (The children of Prometheus) deals with the incredibly long period of human history prior to the invention of writing.

Before we began to write in complex language as a species, we had an entirely different kind of word forms and ecology of communication. These words were early spoken words, but they were not just spoken, they were also performed. We tamed fire, played drums and danced. We went on collective hunts. The reminiscence of such shared memories and experiences as a species, took the form of early Orality, and marked the repetition of specific sounds being ascribed specific meaning in specific contexts. These were sounds, that were closely attached to gestures and movement in the body. Words were felt and not just heard. A sound by itself without the accompanied body gesture wasn’t alive with meaning. It was inanimate and waiting to be performed in order for the true essence of the word to be felt and understood. That we use the word tongue (or Zabaan and Lisans, literally ‘tongues’) in phrases like ‘mother tongue’ and ‘speaking in tongues’, reminds us of the corporeality of the word and the relationship of the utterance with the body.

Shono’s Lisans,handmade sculptural tongue tools are therefore process objects that like rituals bring back the lost performativity of the body into the shared and personal practice of the spoken word. The relegation of Lisans to an ethnographic display form reflects on the slow decay and amnesia of the performative word in our lives and cultures as we seemingly progress.

Mother Tongue, a charcoal print on tape speaks of the loss of memory, identity and knowledge derived from the languages of our elders, that are now long forgotten or in states of disappearance from memories and use. A connected work in charcoal print on tape, Lullaby Departed, is the depth of memory, nostalgia and knowledge held in something as delicate as a mother’s lullaby that has perhaps been lost forever.

As we move from early Orality to more developed oral language systems, record-keeping and collective memory began to take the form of songs. Songs that were sung and passed on across generations. Songs that encoded ancient wisdom and learning. What today constitutes an academic learning through agricultural science, in ancient times took the form of songs and lore through which women for example in Ancient Greece as noted by Noam Chomsky, transferred the science and knowledge of sowing seeds from one generation to the next, while singing songs that encoded said knowledge, as they nice in the field. Those songs and oral traditions of knowing and learning, have long been forgotten. This inability as a species to pass on all learning and knowledge from one generation to the next, is beautifully embodied in Shono’s Our Inheritance of Meaning, a charcoal print on tape, that sees Muhannad use a familiar device in strips of tape as print making bodies that speak analogous to the transference with which we pass on trans-generational learnings, and the underlying decay embedded in such inheritances.

The Silence is Still Talking - Extract, Imprint, Memory and Transfer are four in a series of unique process-based works of study in pigment, tape and paper.

The First and Last Word, a pigment on paper work, encompasses the journey of our relationship with the word in language, in one lifetime and the lifetime of the species. From the early words spoken by mankind to the early words spoken by a child, both nascent and full of association and intent, they develop through the life of the child and leave us to think about the last word that one might utter in their lifetime, and perhaps the last word that we might utter as a species.

CHAPTER THREE

THE WORD, AS WE LEARN AND LEARN AGAIN

An ancient Mesopotamian poem gives us the first known story of the invention of writing.

Because the messenger’s mouth

was heavy and he couldn’t

repeat (the message), the Lord

of Kulaba pattes some clay and

put words on it, like a tablet.

Until then, there had been no

putting words on clay

- Sumerian epic poem Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta (Circa 1800 BC)

THE WRITTEN WORD, LITERAL AND FEARED

Textuality and colonial forces affected the physical world and through language they manipulated conceptual worlds. Non-European sources of knowledge and learning were de-emphasised and some scarce ways of experiencing the world were lost forever. The privileging of enlightenment based streams of knowledge led us through the cancerous effects of uniform and Eurocentric notions of modernity. Similar hegemonies of dominant languages that consume other dialects and marginal language forms exist in our histories across different parts of the world.

Charcoal pigment on black tape works, The Lost Words, represents the erasure of collective knowledge and memory when we choose to foreground certain narratives and sources of knowledge while redacting, censoring, hiding or forgetting others.

The Silent Press

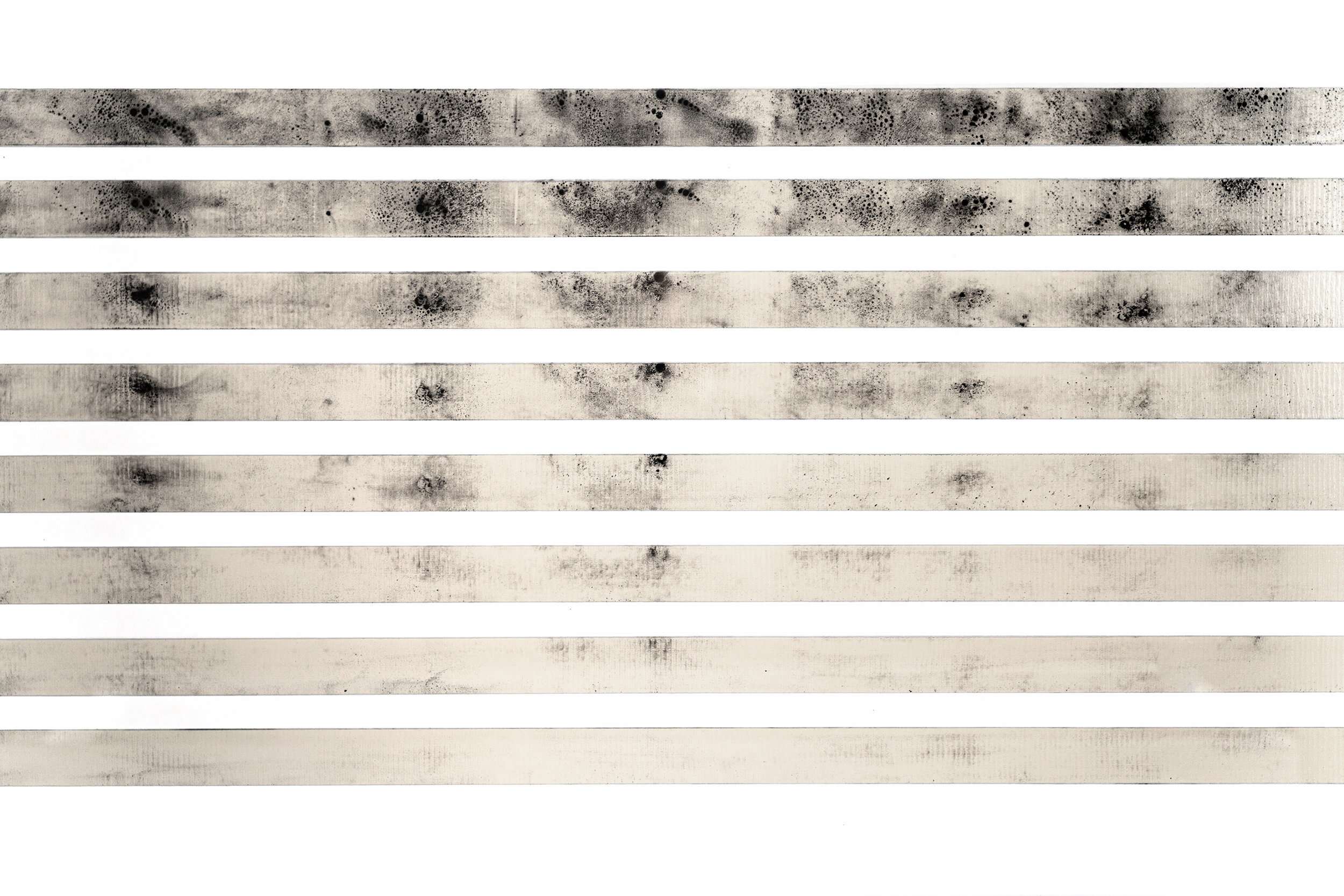

The invention of the printing press by Gutenberg saw serious proliferation of the printed word. The printed word became sacrosanct, the image of the earth as flat was fake news but believed to be true. The representation of the other by European scribes as barbaric and or beastly was immediately believed to be true. It took centuries for us to collectively consider it possible to criticise the written word and question its claims. Meanwhile, solitary critics like Copernicus met a ghastly silence. The free word or the word of the ‘other’ has a history of being feared and persecuted. We’ve noted conquerors and armies burning books and libraries. The fabled library of Alexandria, the writings of Spinoza, the burning of books by Hitler’s forces are familiar examples that bear testimony to the fear of the power of the word by the strongest of forces. The Silent Press, an installation in pigment and paper scrolls is Shono’s response to such erasure, a silent call for the liberation of the word from the hegemony of power, textuality and its restricted dissemination. It also marks the silent memory of the violent erasure of practitioners of the free word and in pregnant pause, awaits and calls for an alternate distribution and dissemination for free words.

THE WRITTEN WORD IS READ BUT ALSO FELT

In the history of words we see the use of symbols, Ideograms, pictograms to communicate complex ideas across histories and cultures from all parts of the world. Ideograms that were sculptural, with depth and lateral meaning, where their context and assemblage, altered meaning. In some cultures the act of writing and reading was (and is) a spiritual act. It was understood that with the use of words came the responsibility to do justice to their depth and to guard against corruption and their abuse. As they learned and evolved in use from numerical systems and accounting tokens, these ideograms and pictograms slowly transformed across some cultures into the use of Cuneiforms, Runes and Phonograms. We see an example of such early writing systems of the Nabateans at Al Ula at Hejaz, in Saudi Arabia. Denise Schmandt-Besserat writes about the history and evolution of early independent writing systems extensively.

Charles K Bliss a Holocaust survivor had witnessed first-hand the brutality of the Nazi regime and the instrumentalisation of words for evil and the mutation of previously well-meaning phrases of unification and nationalism like “Deutschland Zuerst” (Germany First) into words that incited hate and rallied people to commit egregious acts of violence. From his time spent in China and having studied the Chinese Ideograms, and having studied semantics, Bliss, in 1949 devised Bliss symbols. Bliss symbols were ideographic symbols meant for day to day communication that reduced ambiguities in communication and possibilities of misinterpretation. The story of Bliss symbols isn’t all positive however as the symbols become effective tools and technology to teach English to special needs children through sound and symbol association. English being the very kind of existing vulnerable systems of language it seeked to turn away from. While the students gained rudimentary knowledge and communicability in the English language, Bliss symbols for Charles had been corrupted and misused. While ideographic communication was the main cause for the efficacy of these symbols, one of the most compelling features of Bliss symbols was a simple symbol for metaphoric use, that accompanied any arrangements of symbols that were implying metaphorical meaning. Traditional languages in contrast for instance leave us to be the judge of when to employ metaphorical freedom of interpretation.

The alphabet as we know it evolved through a complex set of history and exchange. This history of meaning is lost as we learn the alphabet today in its rigid form to create words. The reemergence of the use of symbols, icons and memes to communicate in digital cultures is an opportunity to remember this history of meaning making and learn from it the dangers of the instrumentalisation or corruption of the word, before we collectively move forward. “In Early Chinese thought ‘Tao or Dao’ is a word that represents ‘The Path’, referring to the ‘way’ of doing, making and (or) being something. For a Butcher the ‘Way of the knife’, is the easiest and the cleanest path to cut through meat. In order for the Butcher to truly learn and embody the path, he or she has to cut and cut again.” (Paraphrased from Yuk Hui’s The question concerning technology in China)

What would similarly be the way of the word?

TO READ AND READ AGAIN

Reading Ring, a sculptural loop of charcoal pigment and ink on paper reflects the re-emergence and reformation of the word with every act of reading. A constant process of study, of reading, of learning and unlearning. The ring invites us to question and re-interpret. For Shono, to illustrate is to read.

Interpretations - I, II, III are a series of readings that illustrate different interpretations from the same landscape of meaning..

A minute reading.

Reformation is one in a series of unique studies of re-reading and revitalising the word.

The essay, The Silence Is Still Talking written by Rahul Gudipudi.

The Silence Is Still Talking

A solo show of entirely new works by Muhannad Shono

Curated by Rahul Gudipudi.

Photo credit Mohammed Askandrani

Athr Gallery, 2019